The article discusses the efforts of citizen scientists and conservationists in New Hampshire to protect local amphibians, particularly during their seasonal migrations. The Salamander Crossing Brigades use modified coolers and lightboxes to photograph salamanders’ unique spot patterns, which can be used to track their movements. Citizen volunteers patrol roads on rainy nights to help move amphibians safely across the road to their breeding grounds, while conservationists use tactics such as amphibian tunnels to protect these animals from road mortality. The article also emphasizes that individuals can make a difference in preserving amphibian populations by starting their own crossing programs or avoiding driving on rainy spring nights. Finally, the article highlights the success of the Salamander Crossing Brigades in influencing local decisions regarding development, and encourages readers to support amphibian conservation efforts.

Nighttime Amphibian Rescue: A Passionate Community Science Effort

Amphibians play a critical role in forest and wetland ecosystems, but their populations are dwindling rapidly, and one of the leading culprits is road mortality. However, everyday people are working passionately to remedy this situation, and they’re having the time of their lives doing it. Brett Amy Thelen ’99, the science director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire, leads a community science project that connects environmental education with conservation research while rescuing these precious creatures.

Thelen supervises the Salamander Crossing Brigades, a group of local volunteers who don warm clothes and reflective vests on specific nights when multitudes of amphibians migrate. On these “Big Nights,” hundreds of volunteers travel to sites in southwest New Hampshire where amphibians cross roads in large numbers. Volunteers carefully ferry these “fun-size” friends across by hand, noting their distinct features like tiny suction cup toes, dark banded legs, and X-shaped patterns on their backs.

One volunteer who braved the steady rain during an unexpected weather change rescued more dead amphibians than live ones. However, with Thelen’s patient, practical demeanor, passion for community science, and love for the outdoors, she has successfully connected environmental education with conservation research while inspiring others to help preserve these vital ecosystems.

Thelen’s Salamander Crossing Brigades, like other community science projects, exemplify the spirit of everyday people working passionately to remedy issues in their communities. With the odds against these amphibians, the Salamander Crossing Brigades and other passionate volunteers make a positive impact on these creatures’ survival while connecting with their communities in a meaningful way.

The Crucial Role of Amphibians in Ecosystems

Amphibians, including frogs, toads, newts, and salamanders, play a critical role in the food web of woodland and wetland ecosystems. They consume large amounts of insects and worms, providing sustenance for countless birds, reptiles, fish, and mammals that would otherwise struggle to survive, especially in the early spring when food sources are limited. Toads, for example, can eat one to three times their body weight in insects each night.

In addition to providing food for other species, amphibians are essential for maintaining biodiversity and the natural cycles that provide clean water, breathable air, and other vital resources. By contributing to the nourishment of a wide variety of species, amphibians help to sustain the complex interactions necessary to maintain a healthy ecosystem.

However, human development has created new challenges for amphibians, and roads have become one of the most significant threats to their survival. Cars crush an estimated 50% to 100% of salamanders attempting to cross rural roads, according to a study by Richard L. Wyman. Road mortality could cause the extinction of local populations of amphibians at their Massachusetts study sites in as few as 25 years, according to researchers from the College of Environmental Science and Forestry in New York.

To address this issue, Brett Amy Thelen ’99, the science director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire, leads the Salamander Crossing Brigades, a community science project that involves volunteers helping amphibians to cross roads during migration season safely. Since 2007, approximately 1,800 volunteers have rescued over 70,000 amphibians in southwest New Hampshire, carefully recording the number of each species they encounter.

This community science project is unique because it not only collects valuable data but also saves the lives of individual animals. Volunteers find the experience of helping to preserve these vital ecosystems to be powerful and fulfilling.

With the decline of amphibian populations, it is essential to continue initiatives like the Salamander Crossing Brigades to protect these species and maintain the critical role they play in the ecosystem.

The Three Conditions for Big Nights

Brett Amy Thelen ’99, the science director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire, uses three factors to predict when Big Nights will occur during the spring migration of amphibians: thawed ground, nighttime temperatures, and wet weather.

Spring-migrating amphibians spend the winter underground. Wood frogs survive the winter by freezing solid, counting on a natural form of antifreeze in their systems to protect their organs while frozen. Most other amphibians stay below the freeze line, which can be up to 60 inches below the surface in New Hampshire. To migrate, amphibians need thawed ground so they can make their way back to the forest floor.

Amphibians are ectotherms, so their body temperature is regulated by the environment. Air temperatures must be at least 40 degrees Fahrenheit for them to be active enough to travel. Lastly, amphibians breathe through their lungs and skin, and they need to stay moist to absorb oxygen through their skin. Therefore, they travel in wet weather.

Thelen closely monitors the weather and provides a five-day salamander forecast during migration season, which volunteers can easily access to see if they should remain on-call. Safety is the top priority for volunteers during Big Nights, so reflective vests and bright flashlights or headlamps are mandatory. Warm layers and rain gear are also essential. Volunteers use clipboards, pencils, and forms on special paper that can be used in rainy weather to record data. Some volunteers bring clean buckets to transport multiple amphibians at once, and cameras and phones are popular items for sharing the experience with friends and family.

Overall, the Salamander Crossing Brigades are a vital initiative to protect amphibian populations and maintain their critical role in the ecosystem. By understanding the three conditions for Big Nights, volunteers can ensure the safety of themselves and the amphibians they are helping to protect.

The Importance of Brigade Volunteers

The Salamander Crossing Brigade depends on volunteers of all ages and professions. These volunteers come from various backgrounds, including lawyers, restaurant workers, nurses, and landscapers. Children as young as six years old are welcome with parental supervision, and some senior citizens have been participating for over 15 years. Most volunteers work in pairs, with one identifying and transporting the amphibians while the other records data.

The adventure begins at sundown, and volunteers can leave anytime they choose. However, some stay until 2 or 3 a.m. before packing up and going home. While it’s important to take data seriously, the Brigade also emphasizes the importance of having fun. According to Brett Amy Thelen, the program director, “If you’re not smiling anymore because you’re cold, wet and tired, it’s time to go home.”

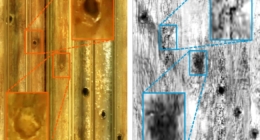

Photographing Spotted Salamanders

Since 2014, Brigade volunteers have had a special mission: photographing individual spotted salamanders. Each of these subterranean species showcases a unique pattern of bright yellow spots on the back of its blue-black body, much like human fingerprints. By comparing photos from previous years to those taken more recently, researchers at the Harris Center have been able to determine that the same salamanders cross at the same site year after year.

The data collected from photographing the spotted salamanders has the potential to provide valuable insight into the year-to-year survival and migration patterns of individuals within the species. However, most of this data has yet to be analyzed, and Thelen believes that it is a veritable treasure trove for just the right graduate student.

The Importance of Salamander Crossing Brigade Data

The Salamander Crossing Brigade, consisting of volunteers of all ages and professions, is a dedicated group of individuals who work to protect migrating amphibians in New Hampshire. Through their efforts, valuable data is collected that is useful in making informed local conservation decisions.

Three Conditions for Big Nights

Brigade member Brett Amy Thelen evaluates three conditions to predict when Big Nights will occur. Spring-migrating amphibians spend the winter below ground, and they must emerge when the ground thaws. Additionally, amphibians are ectotherms, meaning that their body temperature is regulated by their environment. Therefore, air temperatures must be at least 40 degrees Fahrenheit for them to be active enough to travel. Lastly, amphibians breathe through their lungs and their skin. In order to absorb oxygen through their skin, they must stay moist. Thus, they travel in wet weather. Thelen keeps a close eye on the weather and provides a five-day salamander forecast during migration season.

Individual Spotted Salamander Data

Volunteers at five selected sites in New Hampshire photograph individual spotted salamanders each migration season. By comparing photos to those from previous years, researchers at the Harris Center have been able to determine that several of the same salamanders cross at the same site year after year. This data has the potential to provide valuable insight into the year-to-year survival and migration patterns of individuals within the species.

Local Decision Making

Brigade data has been used in local decision making, such as the case of a property in Keene, New Hampshire that was slated for residential development. Brigade data was a significant factor in the decision to deny the development proposal, and the land is now preserved as a valuable amphibian breeding habitat.

Strategies to Combat Amphibian Road Mortality

Conservationists use several strategies to combat amphibian road mortality. Amphibian tunnels installed under roads at crossing sites are one of the most effective. These structures are approximately 2 feet wide, 2 feet deep and topped with an open grating to allow sufficient rain penetration and air circulation. Fencing positioned along the road guides creatures to the tunnel. Although expensive, two tunnels recently installed in Monkton, Vermont cost approximately $400,000, and amphibian deaths are now negligible at that site.

Variable Effort in Data Collection

Thelen explains that their data isn’t necessarily suitable for peer-reviewed studies due to variable effort. Data from sites with fewer volunteers is likely to be less complete than data from sites with more volunteers. Additionally, amphibians that cross in the absence of volunteers are not counted, and some volunteers also prefer not to count dead amphibians, leading to underreported numbers.

Volunteering with the Brigade

Brigade members range from parentally supervised 6-year-olds to senior citizens, and volunteers come from all walks of life. Volunteers work in pairs, with one person identifying the amphibians and the other recording the data. The adventure begins at sundown and lasts as long as volunteers choose to stay. Thelen stresses the importance of safety, reminding volunteers to wear a reflective vest, bring a bright flashlight or headlamp, and dress warmly and in rain gear.

The Salamander Crossing Brigade is a dedicated group of volunteers who work tirelessly to protect migrating amphibians in New Hampshire. Through their efforts, valuable data is collected that has been used to make informed local conservation decisions. Amphibian tunnels have proven to be an effective strategy for combating road mortality, although their cost can be a challenge for decision-makers. Despite some challenges, the Brigade remains committed to their mission, and volunteers of all ages and backgrounds continue to participate in this important conservation effort.

Saving Salamanders: A Community Effort

The spotted salamander is a fascinating and unique species that is under threat due to habitat loss and road mortality. However, in New Hampshire, a dedicated group of volunteers, known as the Salamander Crossing Brigades, are working tirelessly to protect them.

Collecting Data

Brigade members are volunteers from all walks of life, including nurses, restaurant workers, lawyers, and landscapers. Some have been at it for over 15 years, while others are experiencing their first season. Volunteers work in pairs, with one person transporting and identifying the amphibians and the other recording the data. The adventure begins at sundown and lasts as long as the volunteers choose to stay, often until 2 or 3 a.m. Thelen, who leads the brigade, emphasizes the importance of having fun during the night’s events.

The Brigadiers’ primary mission is to photograph individual spotted salamanders. The photographs are then compared to those from previous years, allowing researchers to determine the same salamanders crossing the road year after year. While most of the data collected has yet to be analyzed, the information is a veritable treasure trove that could provide valuable insight into the year-to-year survival and migration patterns of individuals within the species.

Using Data to Make a Difference

The data collected by the Brigades has already been put to good use. For example, when a property in Keene, New Hampshire, was slated for residential development, Thelen shared Brigade data with the local Conservation Commission. The data showed that the property was heavily used by amphibians traveling between their year-round habitat and spring breeding grounds. Thelen’s data, which showed that the Brigade had moved 838 frogs across the road to the property within four hours, was a significant factor in the decision to deny the development proposal. The land is now preserved as a valuable amphibian breeding habitat.

Temporary Road Closures

One of the most significant threats to spotted salamanders is road mortality. Amphibians are particularly vulnerable to being hit by cars during their annual migration. While amphibian tunnels have been shown to be an effective solution, they are also expensive. As a result, many communities opt for temporary road closures.

Thelen made her case for closing North Lincoln Street to the Keene City Council in 2008. Although her request was denied, Thelen continued her work, and the Brigade’s ranks continued to swell. Ten years later, Thelen again stood before the council, this time with 12 years of data showing the need for temporary road closures. The council approved the request, and since then, another stretch of road has been closed on Big Nights. Today, public awareness and the ranks of the Brigade continue to grow, giving New Hampshire amphibians a fighting chance.

The efforts of the Salamander Crossing Brigades are a testament to the power of community action. Through their dedication, the Brigades have helped protect not only spotted salamanders but also the habitats that these unique creatures call home.

Saving Amphibians: How You Can Help

Amphibians play an essential role in the ecosystem, but their populations are declining rapidly due to habitat destruction, climate change, and vehicle mortality. However, there are steps we can take to help save them. If you’re interested in making a difference, there are a few things you can do.

Volunteer on Big Nights

One way to help amphibians is to volunteer on Big Nights. The Salamander Crossing Brigades in New Hampshire, which began in 2007, is one example of how you can make a difference. Volunteers transport and identify amphibians while others record the data. You can check for similar programs in nine other states in the eastern U.S. near you.

Start Your Own Group

If you can’t find an existing program near you, you can start your own group. According to a 2009 study, most crossing sites are within 100 meters of a wetland, so finding potential crossing sites is relatively easy. Look for a stretch of road with a forested hillside on one side and some kind of wetland on the other. But be cautious when driving, as you may end up crushing some amphibians on your way to help others.

Avoid Driving on Rainy Spring Nights

If you prefer not to volunteer outside, you can still save amphibian lives by trying to avoid driving on rainy spring nights. When possible, postpone your errands until tomorrow, as one less car on the road can make traveling safer for our amphibian friends.

Saving the Spotted Salamanders

The Harris Center for Conservation Education in New Hampshire started photographing individual spotted salamanders since 2014. Volunteers use modified coolers known as “lightboxes” to capture the unique pattern of dazzling yellow spots on the back of their blue-black bodies, much like human fingerprints. The collected data can provide valuable insight into the year-to-year survival and migration patterns of individuals within the species.

Road Closures on Big Nights

Closing specific roads on Big Nights is another solution. In Keene, New Hampshire, that means closing roads for four to six nights each spring to allow amphibians to safely cross throughout the entire night. In 2018, the motion to close North Lincoln Street on Big Nights passed, thanks to 12 years of data presented by Brigadiers.

Conclusion

Amphibian populations are declining at an alarming rate. However, there are many ways we can help, such as volunteering on Big Nights, starting your own group, avoiding driving on rainy spring nights, photographing individual spotted salamanders, and closing specific roads on Big Nights. As Laura Grove ’22 says, “Each precious individual that we save can complete its journey to ensure future generations of its species.”

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio