“The Power of Sound Effects: How Audio Is Transforming the Way We Experience Films and TV”

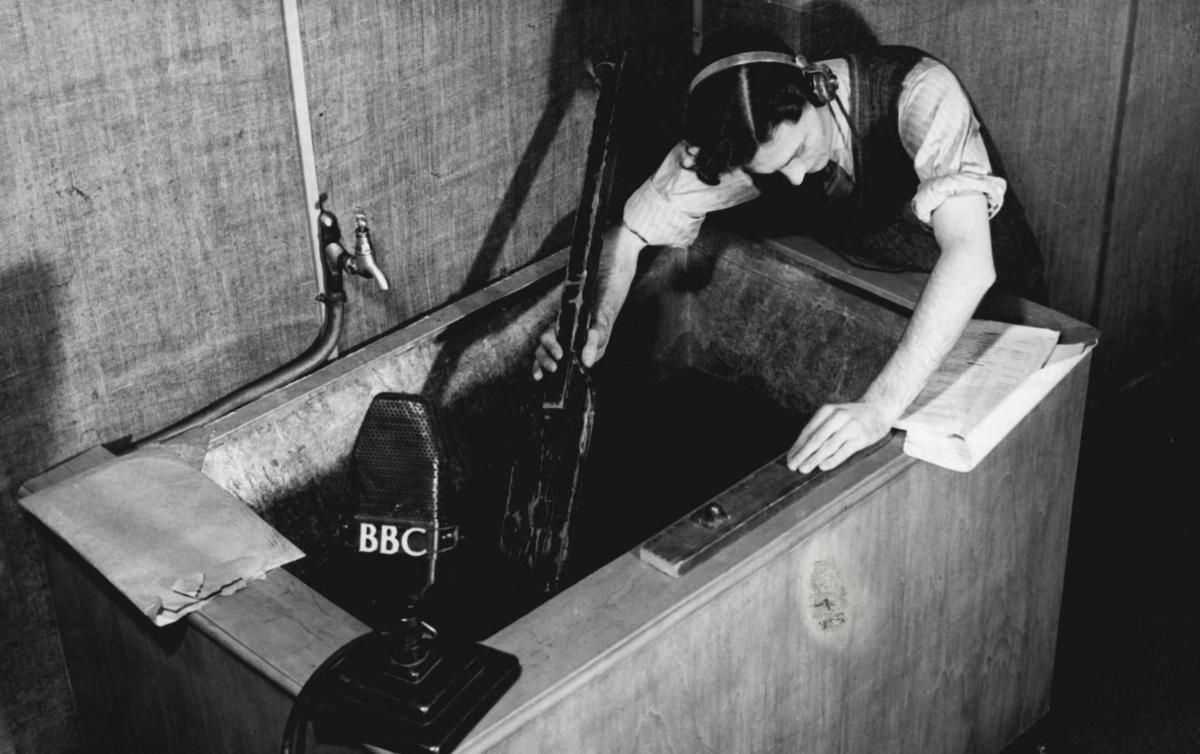

The BBC’s sound effects were originally kept top secret – SuperStock/Alamy Stock Photo

Ah, the unmistakable crackle of a campfire on a summer evening. Or is it actually a foley artist named Ruth Sullivan crunching some plastic between her fingers? In Archive on 4: Knock Knock: 200 Years of Sound Effects (Saturday, Radio 4) took composer and sound designer Sarah Angliss on a journey through the creation of artificial sounds.

Beginning with Thomas De Quincey’s 1823 essay On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth, she traced a sonic path from stage directions to the man who invented the sound of lightsabers and the contemporary sound artists of natural history who breathe icy whistles about recordings of the arctic tundra. The radio play was an important part of the story. Angliss heard how early BBC sound effects techniques were kept in top secret manuals. It was thought that the whole effect would be ruined if the public found out about all the fakes behind the making of the sounds of different types of car engines. These days the BBC Sound Effects archive is freely available online and it’s an open secret that whenever you hear the swish of wellies through mud in The Archers, it’s the audio equivalent of smoke and mirrors.

The interesting thing about Angliss’ program was that, unlike elaborate stage magic tricks, learning how to make sound effects doesn’t spoil the effect at all. Even if you know a fire is crackling plastic, you can still hear the fire. It was fascinating to learn that SFX designer Ben Burtt, who created the otherworldly sounds for the Star Wars films, developed the lightsaber’s distinctive motion-sensitive hum by recording and combining the sounds of his TV and projector, then taking them with him on a microphone he swung around the studio.

For Sullivan, her background as a dancer gave her a sense of rhythm and attention to detail fundamental to creating sound effects. She described watching a silently filmed scene, adding footsteps on stone, characterful door knocks, and the very faint sound a stiffened shirt collar makes when its occupant turns his head in surprise. Kate Hopkins, Sound Editor for Natural History, got a little bit of the Wizard of Oz in Bristol by constructing impressive, completely believable natural settings.

Recorded wind noise is crucial for texturing empty landscapes such as snow-covered deserts or endless savannahs. The different pitches and resonances of the winds make us feel the temperature without even realizing it. The sound of a Siberian explosion can make you tremble, while the winds of a hot sandy desert can almost make you squint at the dust. Forests full of insects and birdsong can be difficult. When she used archival rainforest sounds in the footage that contained the call of a bird not native to the particular area, a bird-loving viewer had to point this out.

Hopkins could be more creative underwater: the sounds here can pulsate, bubble, almost be musical and still feel real. Hopkins gets the greatest compliment when a producer who shot the original material says to her, “That’s what it felt like when I was there.” Knock Knock was perfect radio: atmospheric, bewildering, and verging on an interactive sensory experience. The sound artists demonstrated how sound can have a domino effect on the rest of our senses, changing how we taste, smell, touch and see. It was an exciting argument for the power of sound and how it can deceive and seduce.

Poet Rachel Long – Pako Mera/Alamy Stock Photo

However, not much was said about erotic sounds. Getting the sound of a kiss, especially on the radio, without being gross has to be an ongoing challenge. How do authors manage to convey this powerful but essentially wordless human interaction? In an early Valentine’s Day warmup, poet Rachel Long featured A kiss (Thursday, Radio 4), a literary exploration of how poets put kissing on the page. The program’s central thesis was that a good kiss is like a good poem: impossible to paraphrase or experience otherwise.

There were readings of poetry of varying quality, but oddly most poets were more eloquent on the subject when talking around it rather than reading their works. Perhaps some experiences really do exist beyond sound and word. The most memorable part of A Kiss was a tiny moment of bonding when Long, who is in her 30s, cautiously asked Fleur Adcock, who is in her 80s, if kisses get better with age. Adcock laughed and after a moment’s hesitation replied, “Wait and see.”

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio