(Bloomberg) – Before last week, the stock market was one of the last economic pillars in Turkey, which was largely free from the political whims of the state. That is no longer the case.

Most read by Bloomberg

Through a series of sophisticated, rapid changes, the government injected cash into the stock market and staged a $20 billion rally in its benchmark BIST 100 index over three days. On paper, the BIST 100 index is still near an all-time high, but in reality Turkey has taken another step further from the world of normal finance.

Investors in New York, London and elsewhere say they don’t want to put money into a stock market where the rules change based on who’s in power, but it’s hard to say if the maneuvers are a stopgap during a Crisis or a political one are at play to keep asset prices high ahead of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s elections in May.

“There is no market anymore,” said Wolfango Piccoli, co-president of Teneo Intelligence. “It’s about short-term political goals and endless interference from local authorities using all sorts of tricks to build up a facade of normality.”

Policymakers pulled a variety of levers last week to bolster the stock market, directing private pension funds and government lenders to buy stocks and removing taxes on company buybacks. As a permanent move, Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund plans to create a new mechanism that would allow the government to buy stocks during periods of high volatility.

Mobius warns of boomerang risk as Turkey works to prop up stocks

Some investors warn against reading too much into changes in the days after the worst earthquake in decades. They say it may only be a temporary hiatus, similar to what happens with circuit breakers during times of market stress, and isn’t a sign the government wants an active hand in trading.

“Short-term measures to smooth out market disorder and reduce volatility following the tragic earthquake seem largely warranted,” said Nenad Dinic, equity strategist at Bank Julius Baer. “We see little risk of an unwanted policy of intervention.”

More pessimistic investors are interpreting the changes in the stock markets as an increase in government control that has already reached deep into Turkey’s currency and bond markets.

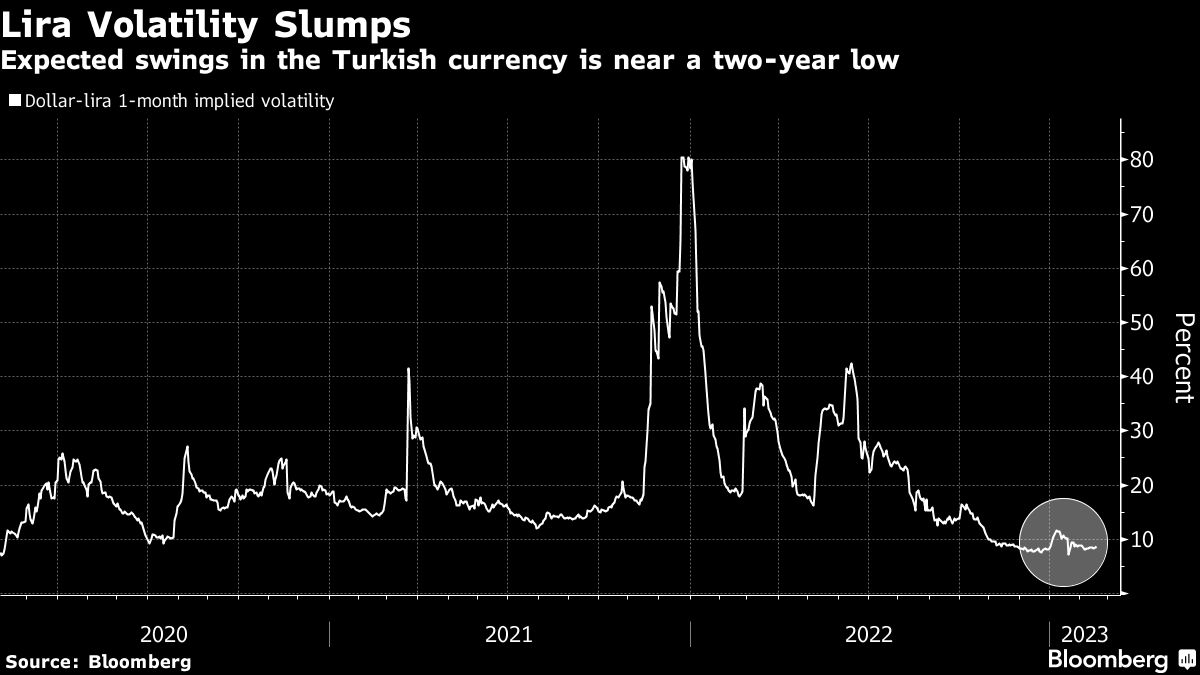

Since Erdogan’s pivotal election in 2018, which gave him vast powers in a new presidential system, the government has employed increasingly unorthodox tactics, from cutting interest rates in times of double-digit inflation to tweaking banking regulation as a backdoor to support the lira.

The result has been an exodus of foreign money from Turkey, which was once a darling of emerging-market investors for its free-market policies.

According to data from clearing house Takasbank, foreign investors now hold only about 30% of Turkey’s stocks, compared to an average of 60% over the past two decades. For bonds, foreign ownership is almost 1%, compared to 28% in 2013.

In the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, Turkish companies make up around 0.5% of the benchmark. That puts it on par with Chile, whose economy is about half the size.

Contingency measures pushed the BIST 100 up 12% this week, and the index has more than doubled in lira terms since early 2022. In Turkey, where the government keeps interest rates and deposit rates artificially low and bonds yield far less returns than inflation, stocks and gold are some of the few logical havens for savings.

For international investors, the changes in Turkey’s stock market have increased the risk that regulations will turn the country into a more closed market, mostly relevant to locals. Before the earthquakes, the BIST 100 was the worst-performing stock market in the world that year.

According to Nick Stadtmiller, head of product at Medley Global Advisors in New York, it will be difficult for the government to keep the stock market high through constant intervention.

“The problem is that the stock market will almost certainly need fresh buying to stay at high levels,” he said. “Officials will need to continue to intervene to prevent a stock market meltdown that would hurt consumer sentiment and spending.”

Other investors have shrugged off concerns about investing in Turkey, saying it’s part of the risk that comes with emerging markets. Carlos Hardenberg, portfolio manager at Mobius Capital Partners, said he was keeping Turkey’s equity holdings steady and waiting to see how the election unfolded.

“We have seen this in other countries as well and the measures are temporary,” he said. “Obviously, regulators should generally stay out of the market as that would lead to a loss of confidence.”

Most Read by Bloomberg Businessweek

©2023 Bloomberg LP

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio