“Indigenous Alert System in Washington State Sheds Light on Missing and Vulnerable”

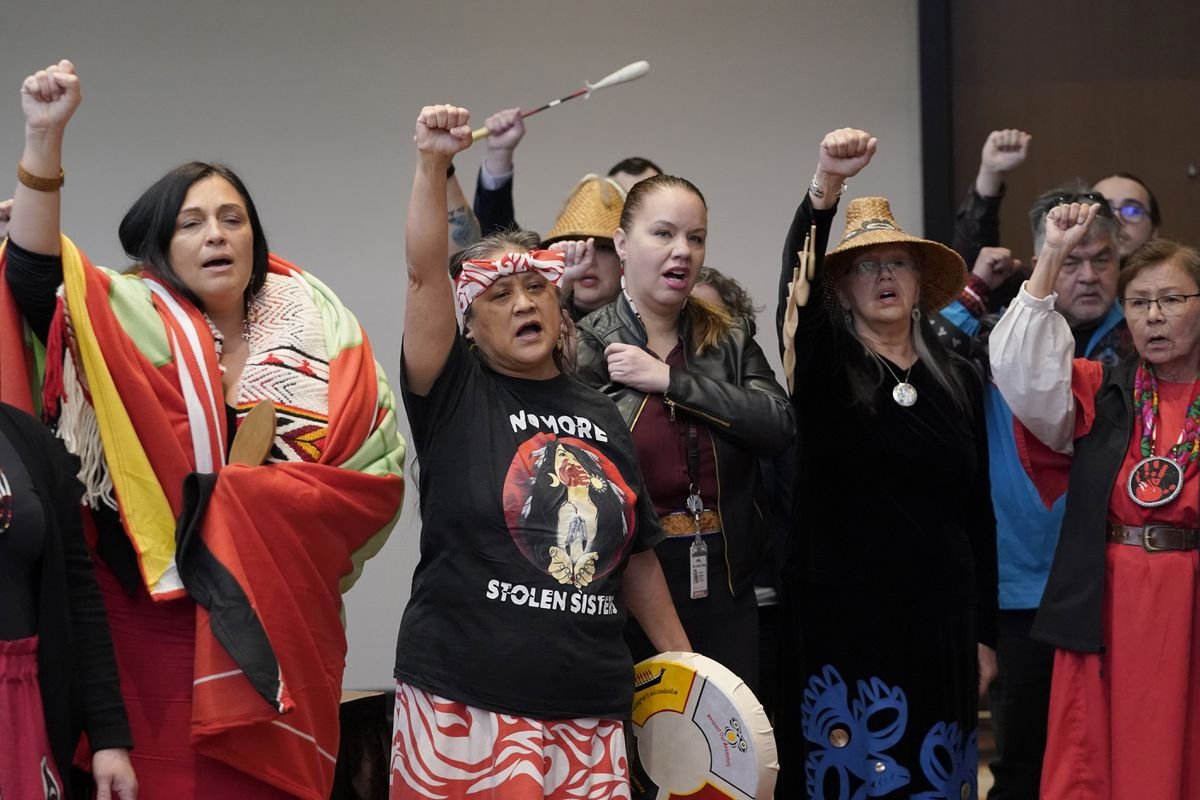

Monie Ordonia, second from left, of the Tulalip Indian tribe, joins others in singing a song of honor after Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed legislation March 31 creating a first nationwide alert system for missing Indigenous peoples , 2022, in Quil Ceda Village, near Marysville, Washington. Ted S Warren/The Associated Press

A groundbreaking missing tribal peoples alert system has drawn new attention to a group that has historically felt ignored by authorities, part of a broad reckoning reshaping Washington state’s relationship with tribal communities.

It is a change that is beginning to expand its reach. Other states are now replicating the new alert system, which proponents say Canada should also consider.

But its creation has also brought new problems to light as authorities scramble to raise local police awareness of the new tool and work with neighboring states to find the vulnerable.

It’s a bit like a baby taking its first steps, says Debra Lekanoff, a Democratic state official who is a member of the Tlingit tribe and helped create the new system. It has recently completed its first six months of operation.

“We falter. we fall down And we pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off,” she said in an interview.

The system, which gives police the ability to send information quickly without having to meet the strict criteria for Amber alerts, was criticized for not taking action in some cases, while its proponents struggled to persuade some local authorities to participate. It has highlighted limitations in how police departments across state lines work together to track missing persons and claims to have had only modest results in helping find missing persons: Out of 43 alerts, all but five people were found – but only four, which the authorities assign directly to the system.

Some have questioned its effectiveness, saying they have seen more success with missing persons leaflets.

But Washington’s Warnings of missing tribal people have also recalibrated law enforcement mechanisms to respond with renewed urgency to cases that had once languished. Before the alert system went live on July 1, 2022, it could take several days for authorities to be notified of a missing tribal person.

“When the first alarm went off, we were able to complete this process in less than 30 minutes,” said Annie Forsman-Adams, policy analyst with the Washington State Task Force on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People.

“For the first few alerts, we found people very, very quickly,” she said.

“So I think it’s really a useful tool for doing what it needs to do.”

Indigenous women turn to TikTok to keep unsolved missing persons and murder cases in the spotlight

The idea spread quickly. In January, Colorado and California introduced their own systems, which California has dubbed “Feather Alert.” Authorities in New Mexico, Michigan and Minnesota have also shown interest.

In Washington, the warnings are part of a broader attempt by lawmakers and attorneys to open authorities’ eyes to longstanding injustices. The Washington State Patrol now maintains a list of missing tribal peoples, which it releases every two weeks. The task force, established in 2021, has recommended new ways for authorities to work together on behalf of services to indigenous communities.

“We raised awareness,” said Representative Lekanoff.

The underpinning of the alert system is a major mindset shift where the state decides to treat a missing Indigenous person as a missing person at risk.

For an Indigenous woman in the state, there’s a renewed sense of security knowing that if she’s missing, “the person at the grocery store is looking for me, the NFL Seahawks coach is looking for me.” Everyone’s looking for me,” Ms. Lekanoff said.

The Washington State Patrol partially credits Canada with bringing the issue of murdered and missing Tribal peoples to the forefront of national attention.

But the state’s ambitious response to the problem has also shed a critical new light on Canada, where the most comprehensive national database of missing tribal peoples is Aboriginal Alert, a website run by Dan Martel, a Métis consultant in Edmonton. His tight budget is mostly funded by his own business, with some additional funding from the province of Alberta. His most effective notifications are boosted posts on Facebook, which he buys for $5 each.

It is very different from the state police resources dedicated to the Washington Alert System.

“There’s more coming out of Washington than I’ve seen in Canada,” he says.

Carri Gordon is at the center of this effort. As the Missing Persons Coordinator for the Washington State Patrol, she has worked with Amber Alerts since 2004. Raising public awareness of missing tribal peoples requires rethinking how public alerts are issued, she said. Police are often accustomed to working with amber alerts, which require a known kidnapping and a reasonable assumption that the person cannot return to safety without assistance.

“There’s often a lack of immediacy in the indigenous warnings,” she said.

It’s a unique warning.

“The only requirement is racial demographics,” said Patti Gosch, a tribal liaison with the Washington State Patrol. The alert can only be activated by a law enforcement request, and that may be a long time coming. An eight-year-old Indigenous child went missing the day before Ms Gordon spoke to The Globe and Mail at 3pm.

“We didn’t receive an emergency call until midnight. That’s not okay,” she said.

Other frustrations have surfaced as well. Las Vegas police, for example, don’t use the National Crime Information Center, a centralized registry of fugitives and missing persons. This has made it difficult to trace tribal peoples who have disappeared there.

In Washington, meanwhile, state police are reluctant to use cellphone alerts when Tribal peoples go missing, wary of generating public inattention by overusing the system. But that has limited its reach. “I don’t know how well it’s working because I haven’t seen those notifications,” said Teri Gobin, CEO of the Tulalip Tribes.

Tulalip Police Chief Chris Sutter has found that local networks are more effective. “We create our own missing persons flyers and send them out to our community through our tribal social media persona,” he said. “And that usually brings a lot more feedback and tips.”

Nevertheless, the warning system has produced tangible successes. A friend told Ms. Lekanoff that she saw a green minivan on a remote road shortly after passing road warning signs describing a missing Indigenous person in a vehicle of that description. The friend reported the vehicle and the person was found. The broader government focus on missing Indigenous people has also solved very old cases. One person was located 57 years after they were reported missing.

“The whole point of what we do is to enable families to graduate when and where we can,” Ms. Gosch said.

The attorney general’s office plans to create a contingency unit dedicated to missing tribal peoples this year, and other attempts to redress the marginalization of tribal peoples in law enforcement are underway. New procedures will result in tribal police being trained at the same academy as other officers, allowing them to enforce state law outside of the reserve. (In some other states, the segregation is so great that tribal police officers who drive their vehicle off the reservation can be arrested for posing as an officer.)

“We learn a lot that we didn’t know before. Because the cops generally weren’t paying attention, I don’t think so,” Ms. Gordon said.

In Canada, meanwhile, the RCMP says it is not responsible for creating new types of alerts as that falls to the provinces and territories. “The decision to establish a new public alert for a specific group is not made by the RCMP,” Corporal Kim Chamberland, a spokeswoman, said in a statement.

Mr. Martel, the founder of Aboriginal Alert in Canada, does not see police alerts for missing Indigenous people as a panacea. But he’d still like to see Canadian authorities take the idea more seriously, combined with the work he’s already doing – which could also benefit from more provincial funding.

“You guys do the alarm system,” he said of the government. “Put up the signs. We’ll get the moccasin telegraph going. And we will solve that.”

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio