Increasing prevalence of a condition does not necessarily mean a true increase in the prevalence of the condition. The number of diagnoses increases as the search for the disease or medical condition intensifies. This is likely to happen for a condition that has no biochemical or tissue test to determine the diagnosis, like autism spectrum disorders. The diagnostic criteria for diseases are also subject to change, leading to more diagnoses of conditions like hypertension and thyroid cancer. Prevalence increases involve both increased screening and changes in the diagnostic criteria. It is more likely that we are getting better at finding and diagnosing autism, including milder cases, rather than a massive increase in the “true” prevalence of autism. The consensus is that the evidence rules out the sorts of massive increases that antivaxxers claim and then blame on vaccines. Instead, differences in the “true” prevalence of autism attributable to race, gender, and ethnicity are likely to occur, as they do for many medical conditions and diseases, without vaccines as a root cause.

Autism Prevalence Increases to 1 in 38, with Antivaxxers Pointing Fingers at Vaccines without Explicitly Saying So

In the past, the antivaccine movement had a central conspiracy theory that vaccines were the cause of autism, and that the evidence was being covered up by the CDC and FDA. Although that theory seems mild in comparison to today’s claims about COVID-19 vaccines, it was still prevalent during National Autism Awareness Month every April. The movement linked a combination of the MMR vaccine, “too many vaccines too soon,” and mercury from the thimerosal preservative used in childhood vaccines before 2001 as the primary cause for the “autism epidemic.” However, other supposed causes such as processed foods and wifi were also added, but vaccines were always at the center of the blame for the increasing autism prevalence.

According to recent statistics, the autism prevalence has increased to 1 in 38, a significant rise compared to the previous 1 in 59. However, antivaxxers refuse to acknowledge vaccines as the cause and instead point fingers at processed foods and environmental factors. Despite this shift in blame, the link between vaccines and autism has been thoroughly debunked by numerous studies and scientific evidence.

The antivaccine movement’s central conspiracy theory has since evolved, and they now claim that COVID-19 vaccines, particularly mRNA vaccines, are responsible for killing, sterilizing, and inducing “turbo cancers” in millions of people. These claims are without evidence and unsupported by any credible sources. However, the movement persists in spreading misinformation about vaccines, causing harm to public health.

In conclusion, while the antivaccine movement has shifted its focus from vaccines causing autism to COVID-19 vaccines, their claims remain unsupported by evidence. Vaccines have been proven to be safe and effective, and the rise in autism prevalence is likely due to increased awareness and better diagnosis, rather than vaccines.

Antivaxxers Blame Vaccines for Autism without Saying the Word “Vaccine”

While the rise of COVID-19 vaccines has fueled the “new school” antivaxxer movement, there is increasingly little difference between these individuals and “old school” antivaxxers who blame vaccines for autism. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence proving the safety and efficacy of vaccines, antivaxxers continue to link the MMR vaccine, “too many vaccines too soon,” and mercury from thimerosal as the root cause of the “autism epidemic.”

In a recent article by Cynthia Nevison on Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s website, the title “In New Autism Report, CDC Again Fails to Address Root Causes” suggests that vaccines are to blame for autism. However, Nevison never explicitly uses the words “vaccine” or “vaccination” in her article, demonstrating a shift in antivaxxer language. Instead, she attacks public health organizations like the CDC for being too “woke” and focusing on equity rather than causation.

Meanwhile, Brenda Baletti’s article on the same website, entitled “1 in 36 Kids Have Autism, CDC Says — Critics Slam Agency’s Failure to Investigate Causes,” refers to “environmental factors,” but the main focus is on vaccines as the cause. However, the rise in autism prevalence is more likely due to increased awareness and better diagnosis, rather than vaccines.

Antivaxxers have co-opted the language of scientists and skeptics to liken those who deny the link between vaccines and autism to climate science deniers. They also attack public health organizations for being too focused on equity and not enough on causation. However, the scientific evidence is clear: vaccines are safe and effective, and do not cause autism.

In conclusion, antivaxxers continue to blame vaccines for autism, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The shift in language to avoid using the word “vaccine” demonstrates a realization that their claims are unfounded and unsupported by science. It is important to continue to educate the public about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and to combat misinformation from the antivaxxer movement.

Environmental Risk Factors for Autism: Metals in Vaccines, Glyphosate Exposure, and More

Research has explored the role of environmental risk factors in the increasing prevalence of autism among children in the US over the past few decades. These risk factors include metals such as aluminum and mercury found in vaccines, glyphosate exposure, and the use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and infancy. Heavy metals in baby food and other organic environmental pollutants are also cited as potential risk factors for autism.

In addition to these factors, studies have linked industrial chemicals like lead, arsenic, copper, selenium, iron, and magnesium to autism. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence debunking the link between vaccines and autism, the antivaccine movement continues to blame vaccines for the disorder’s rising prevalence.

Antivaxxers have been vocal about their beliefs regarding vaccines and autism, with concern reaching its peak during the CDC’s reported autism prevalence of 1 in 59 in 2018. However, scientific evidence suggests that the true prevalence of autism has remained unchanged over the past two or three decades.

In conclusion, research has identified several environmental risk factors for autism, including metals in vaccines, glyphosate exposure, and heavy metals in baby food. Despite this evidence, the antivaccine movement continues to link vaccines to the disorder’s prevalence, despite scientific evidence disproving this link.

Antivaccine activists have been using the rising prevalence of autism in the US to propagate their belief that vaccines cause autism. According to them, there is an autism “epidemic,” and they often liken it to a natural disaster like a tsunami, with vaccines being the root cause. This narrative has been around since the 1990s, and any scientific pushback against this claim is quickly dismissed as denial.

As the CDC releases new figures for autism prevalence every year, antivaxxers often use this opportunity to reiterate their argument that environmental factors, including vaccines, are the primary cause of the increase. While it’s true that environmental factors can alter the risk of developing autism, evidence indicates that genetics play a much more significant role. The largest contributor to autism is believed to be genetic, with environmental factors contributing between 7% to 35% and possibly even as low as zero. Recent studies have also found signs of autism in fetuses, further reinforcing the genetic component.

Despite this evidence, antivaxxers continue to propagate the belief that vaccines cause autism. They have co-opted the language of scientists and skeptics to make their claims sound legitimate. They are attacking public health organizations like the CDC for not investigating the so-called “root causes” of autism, which they claim are vaccines and other environmental factors. However, changing times lead to changing language, and they have become more clever in avoiding the use of words like “vaccine” or “vaccination” to hide their true intentions.

The antivaccine narrative linking vaccines to autism continues to persist, and it’s time to update the public on the evidence that shows otherwise. While environmental factors may play a role, genetics are the most significant contributor to autism. It’s time to stop the misinformation and focus on the evidence.

The CDC recently released its report on autism prevalence, covering up to 2020. The report analyzed data from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, which provides estimates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) prevalence among 8-year-old children in the United States. The report indicated that autism prevalence had increased to 1 in 44 children, up from 1 in 54 children in the previous report in 2016. However, it is important to note that this increase may be attributed to improved diagnosis and screening methods rather than a true increase in prevalence.

Active surveillance is crucial in monitoring for a diagnosis

Active surveillance is crucial in monitoring for a diagnosis, as opposed to passive surveillance systems that rely on reports generated by healthcare workers and other sources. Active surveillance systems are set up to monitor for a diagnosis. In the case of ADDM, trained clinicians visit schools and healthcare providers to collect information on children’s behaviors and development. They then review and classify the data using standard diagnostic criteria to identify children with ASD. This process allows for more accurate and comprehensive monitoring of autism prevalence.

Genetics play a significant role in autism prevalence

Although environmental factors such as exposure to toxins and pollution may contribute to autism development, research suggests that genetics play a significant role in autism prevalence. The disorder is multifactorial, with estimates of the contribution of environmental factors ranging from 7% to 35%. However, the majority of evidence points to genetic factors as the primary cause. This conclusion has been reinforced by recent studies and the detection of signs of autism in fetuses.

In conclusion, the CDC’s latest report on autism prevalence highlights the importance of active surveillance in accurately monitoring the disorder’s prevalence. While the increase in prevalence may be due to improved diagnosis and screening methods, the research suggests that genetics play a significant role in autism development. The evidence supports the conclusion that autism is primarily genetic, with environmental factors playing a smaller role.

One in 36 children aged 8 years estimated to have ASD

The latest report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that approximately 1 in 36 children aged 8 years in the United States was estimated to have autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in 2020. This translates to roughly 4% of boys and 1% of girls. These estimates were higher than previous estimates reported by the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network during 2000-2018.

Racial and ethnic differences in ASD prevalence

The report also revealed that the prevalence of ASD was lower among White children aged 8 years than among children of other racial and ethnic groups. This reversal marks the first time that White children with ASD had a lower prevalence than children of other racial and ethnic groups. However, Black children with ASD were still more likely than White children with ASD to have a co-occurring intellectual disability.

Study design and key findings

The ADDM Network staff reviewed and abstracted developmental evaluations and records from community medical and educational service providers in 11 sites across the United States to ascertain ASD among children aged 8 years. A child met the case definition if their record documented 1) an ASD diagnostic statement in an evaluation, 2) a classification of ASD in special education, or 3) an ASD International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code.

Prevalence was calculated as the number of children with ASD per 1,000 children in the defined population or group. The report found that overall ASD prevalence estimates included all children with ASD from all 11 sites. Prevalence was also stratified by sex and by race and ethnicity using both the U.S. Census postcensal population estimates as well as the National Center for Health Statistics postcensal bridged race denominators. Statistical tests with p values <0.05 and prevalence ratio 95% CIs that excluded 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

Exploring the Link Between Race and Autism Prevalence

According to a recent report published by the CDC, the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) among children aged 8 years has continued to increase. The data was collected from 11 ADDM Network sites across the United States and was based on diagnostic statements, special education classifications, and ASD International Classification of Diseases codes. For the year 2020, the overall prevalence was 27.6 per 1,000 children aged 8 years, with boys being 3.8 times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with ASD. Additionally, ASD prevalence varied among different races and ethnicities, with non-Hispanic White children and children of two or more races having a lower prevalence than non-Hispanic Black or African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander children.

The report also highlighted an important finding that for the first time, ASD prevalence was lower among non-Hispanic White children and children of two or more races than among non-Hispanic Black or African American (Black), Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander (A/PI) children. The difference in prevalence between white and Black children was previously attributed to disparities in access to screening, health care, and services, leading to under-ascertainment of cases among minorities. However, the lower prevalence among certain races and ethnicities has caught the attention of anti-vaccine advocates, who link it to vaccinations.

A recent article by one such advocate, Gayle DeLong, published on the website of a leading anti-vaccine movement, cites the CDC report as evidence of a rapid rise in ASD prevalence among racial minorities relative to white children. However, it is essential to note that the author did not explicitly mention vaccines but referred to “environmental factors” or “non-genetic factors” that could potentially contribute to ASD prevalence. The author denies being anti-vaccine but has a history of linking vaccinations to autism.

It is crucial to note that the CDC report does not establish a causal link between vaccines and autism. The lower prevalence of ASD among certain races and ethnicities could be due to multiple factors, including disparities in access to healthcare, genetic factors, or environmental factors. Nonetheless, the report serves as a call to action to identify and address the disparities that exist in ASD diagnosis and care, particularly among minority populations.

In conclusion, the recent CDC report on ASD prevalence highlights the need to explore the link between race and ASD diagnosis, and address the disparities that exist in accessing healthcare and diagnosis. It is crucial to avoid drawing unwarranted conclusions and instead focus on evidence-based approaches to identify and address the factors contributing to ASD prevalence.

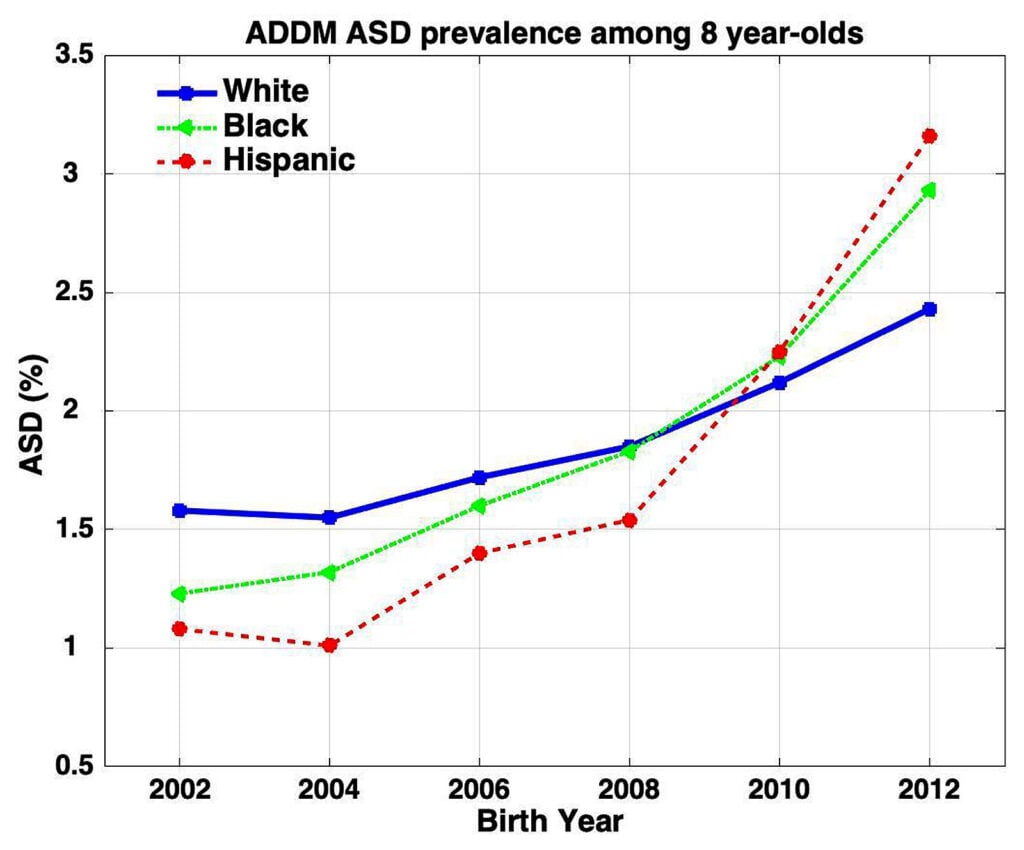

The mean ratio of Hispanic to white and Black to white autism spectrum disorder (ASD) prevalence has increased significantly, according to new reports by the CDC. The mean Hispanic to white ASD ratio has increased from 0.67 in 2004 to 1.3 for 8-year-olds and 1.8 for 4-year-olds. Meanwhile, the mean Black to white ASD ratio is 1.2 for 8-year-olds and 1.6 for 4-year-olds. Figure 1 illustrates the increase in ASD prevalence across all racial groups. However, the prevalence rate for whites is increasing at a slower rate than other racial and ethnic groups.

Nevison criticizes media coverage that attributes the increasing ASD prevalence rate among Black children to better diagnosis. The media implies that the overall increased rate of ASD among racial minorities is a positive development because it indicates that these children are catching up to whites in terms of diagnostic equity. However, Nevison argues that this interpretation is based on the underlying assumption that there is a natural genetic level of ASD in the population reflected in white prevalence. The new ADDM report shows that the prevalence of ASD is now lower among white children than among other racial and ethnic groups, reversing the direction of racial and ethnic differences in ASD prevalence observed in the past. The report fails to acknowledge that this reversal undermines the hopeful interpretation of previous ADDM data and effectively turns the equity argument on its head.

The new CDC reports also found that ASD prevalence was associated with lower household income at three sites, indicating that socioeconomic factors play a role in the development of ASD. The reports provide valuable insights into the prevalence of ASD among different racial and ethnic groups and the impact of socioeconomic factors. The increase in ASD prevalence among racial minorities highlights the need for better outreach and screening programs to ensure that all children, regardless of race or ethnicity, receive early diagnosis and access to services.

Nevison’s Interpretation of the CDC Report on ASD Prevalence among Racial and Ethnic Groups

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has revealed that the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is higher among minority children in the US compared to non-Hispanic white children. The CDC report examined ASD prevalence rates among 8-year-old and 4-year-old children born in 2016, across 11 Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) sites in the US.

Racial Disparities in ASD Prevalence

According to the CDC report, the prevalence of ASD among Hispanic children was 1.3 times higher than that of non-Hispanic white children. Similarly, the prevalence of ASD among Black children was 1.2 times higher than that of non-Hispanic white children. Meanwhile, the prevalence of ASD among Asian or Pacific Islander children was 1.6 times higher than that of non-Hispanic white children.

Notably, the report found that the prevalence of ASD was lower among non-Hispanic white children and children of two or more races than among non-Hispanic Black or African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander children. This reversal of the trend observed in previous reports indicates that the racial disparities in ASD prevalence have shifted over time.

Nevison’s Interpretation

Christine Nevison, an epidemiologist and research scientist, critiques the interpretation of the CDC report by antivaxxers, who dismiss the possibility that the increase in ASD prevalence observed among Black children is due to better ascertainment. Nevison argues that the increase in prevalence among underserved minorities is actually an indication that these groups are finally getting access to screening and services that white children have long taken for granted.

Nevison also challenges the assumption that there is a “natural genetic level of ASD in the population” reflected in the prevalence in white children. Instead, she suggests that differences in prevalence among racial and ethnic groups for heritable conditions like autism could be expected, just as with diseases with a large genetic component like various cancers and cardiovascular diseases.

Finally, Nevison highlights the overlooked and unmentioned disparity in the rate of co-occurring intellectual disability, which is nearly twice as high among Blacks compared with whites. She argues that this thorn doesn’t fit with the optimistic “catching up” interpretation of the CDC report.

Conclusion

The CDC report on ASD prevalence among racial and ethnic groups in the US highlights the need for continued efforts to ensure access to screening and services for underserved minority groups. While some antivaxxers have dismissed the increase in prevalence as due to better ascertainment, epidemiologists like Nevison stress that disparities in prevalence among racial and ethnic groups for heritable conditions like autism are expected. It remains crucial to address the disparities in prevalence and co-occurring intellectual disability among different racial and ethnic groups, and to work towards providing equitable access to screening and services for all children.

According to a new ADDM report, more than 60% of the 8-year-olds diagnosed with ASD nationwide have either severe or borderline co-occurring intellectual disability. Among Black children, more than 75% have severe or borderline co-occurring intellectual disability. Although Nevison overlooks a significant limitation of the study that the surveillance case definition of intellectual disability is not equivalent to a clinical diagnosis and IQ measurements in young children might lack stability, antivaxxers dismiss the possibility of under-ascertainment of ASD among Black children without intellectual disability, which is a perfectly reasonable possible explanation that needs to be considered and investigated. Antivaxxers like Sallie Bernard try to spin the high rate of intellectual disability and borderline intellectual disability in Black children with ASD as evidence of an environmental cause of autism, while others like Toby Rogers claim that the CDC is concealing the truth.

In the same report, it was found that the mean Hispanic to white ASD ratio is 1.3 for 8-year-olds and 1.8 for 4-year-olds, while the mean U.S. Black to white ASD ratio is 1.2 for 8-year-olds and 1.6 for 4-year-olds. Figure 1 of the report highlights how these racial differences in ASD prevalence have shifted over time. Although the absolute prevalence continues to rise for all racial groups, the reversal of the direction of racial and ethnic differences in ASD prevalence observed in the past, as noted in the report, undermines the hopeful interpretation of previous ADDM data and effectively turns the equity argument on its head.

The report recognizes that observing underserved minorities “catch up” in prevalence is likely an indication that these groups are finally receiving access to screening and services that white children have long taken for granted. However, antivaxxers like Sallie Bernard dismiss the possibility that the increase in ASD prevalence among Black children in the latest report is due to better ascertainment, claiming that no racial or ethnic minority gets better assessment and diagnosis than white children. This assumption ignores the fact that assessment and diagnosis do not have to be “better” to produce such a result in a single year’s study, particularly if the actual prevalence in Black children is higher than it is in white children.

In conclusion, the new ADDM report reveals that Black children with ASD are more likely to have a co-occurring intellectual disability. While there could be various reasons for this, including under-ascertainment of ASD among Black children without intellectual disability, antivaxxers spin the report to advance their own agendas.

Toby Rogers, an antivaccine activist, was criticized for cherry-picking studies to support his claim that there is an unidentified environmental contributor to autism. Steve Novella pointed out that the studies used by Rogers had flaws, and he ignored studies that show the increase in ASD prevalence is due to changes in diagnostic criteria, screening, and public awareness. The vast majority of increases in ASD prevalence are driven by these factors, which lead to differences in the proportion of children who receive an ASD diagnosis. Antivaxxers often argue that such large increases in diagnosis cannot be explained by changes in diagnostic criteria and/or screening, but the example of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) shows how this argument is flawed. Before 1975, DCIS was very rare because by the time it became a palpable mass, it had almost always become invasive cancer. Now, DCIS is a common diagnosis due to the introduction of mammographic screening, which has led to a more than 16-fold increase in incidence over a 30 year period.

In the new birth year 2012 ADDM report, more than 60% of the 8-year-olds diagnosed with ASD nationwide have either severe (IQ < 70) or borderline (70 < IQ < 85) co-occurring intellectual disability. Among Black children, more than 75% have severe or borderline co-occurring intellectual disability. However, the surveillance case definition of intellectual disability is not the same as a clinical diagnosis, and IQ measurements in young children might lack stability, so children might not ultimately receive a diagnosis of intellectual disability. There could well be other reasons for the high rates of co-occurring intellectual disability in Black children with autism, and further investigation is needed. Antivaxxers like Sallie Bernard and Toby Rogers dismiss the possibility that the increase in ASD prevalence observed among Black children is due to better ascertainment and instead spin conspiracy theories about environmental causes.

The racial differences in ASD prevalence have shifted over time, with the mean Hispanic to white ASD ratio at 1.3 for 8-year-olds and 1.8 for 4-year-olds in the new reports, while the mean U.S. Black to white ASD ratio is 1.2 for 8-year-olds and 1.6 for 4-year-olds. The prevalence of ASD was lower among White children than among other racial and ethnic groups for the first time, reversing the direction of racial and ethnic differences in ASD prevalence observed in the past. The authors of the ADDM report did not acknowledge that this reversal undermines the previous “catching up” interpretation of the birth year 2006 and 2008 reports, which implied that Blacks were achieving diagnostic equity. The increase in autism prevalence among Black and Hispanic children is actually likely an indication that these groups are finally getting access to screening and services that white children have long taken for granted.

The prevalence of various conditions has increased in recent years, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that the actual number of people with the condition has increased. For example, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a type of breast cancer, was very rare before mass mammographic screening programs became prevalent, but now it is a common diagnosis. Approximately 40% of breast cancer diagnoses are DCIS, and a recent study found that DCIS incidence rose from 1.87 per 100,000 in the mid-1970s to 32.5 in 2004. This 16-fold increase over a 30-year period was mainly due to the introduction of mammographic screening. Hypertension is another condition whose prevalence has increased over the years, but this is largely because of changes in diagnostic criteria and increased awareness among doctors. For example, before the 1920s, hypertension was very uncommon because doctors weren’t routinely measuring systolic/diastolic blood pressure ratios.

The increase in diagnoses can also be seen in conditions like thyroid cancer, which has increased significantly due to increased screening with ultrasound. However, the vast majority of these diagnoses are likely due to overdiagnosis. In general, diseases for which the prevalence is increasing often involve both increased screening and changes in the diagnostic criteria.

It’s important to note that increasing numbers of diagnoses does not necessarily mean that the actual number of people with a condition or disease has increased. Overdiagnosis and changes in diagnostic criteria can play a significant role in the increase in diagnoses.

Increasing prevalence of a condition merely indicates an increase in the number of people given a diagnosis, and not necessarily an actual increase in the condition’s prevalence. If more intensive screening is performed for a disease or medical condition, it will always reveal more of it. The same is true for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), especially since their diagnostic criteria have changed significantly over the past three decades to be more comprehensive.

While it is possible that there has been an actual increase in the prevalence of autism over the past few decades, recent evidence indicates that this is not the case. The increase in autism diagnoses is most likely due to improved detection and diagnosis of autism, including milder cases. As a result, the apparent prevalence of autism (i.e., the number of diagnoses) is starting to converge on the “true” biological prevalence of autism as it is currently defined. In addition, it is possible that the “true” prevalence of autism varies by race, gender, and ethnicity, as is the case for many medical conditions and diseases.

This does not mean that vaccines are the root cause of autism, as antivaxxers often claim. The consensus among experts is that vaccines do not cause autism, and the evidence supports this. The increasing prevalence of autism is more likely the result of increased awareness and understanding of the condition, as well as improvements in diagnostic tools and techniques.

In conclusion, the increasing prevalence of a medical condition does not necessarily mean that the condition itself is becoming more prevalent. Instead, it may indicate that we are becoming better at detecting and diagnosing it. With respect to autism, the evidence indicates that improved diagnosis is the primary driver of the apparent increase in prevalence, and that vaccines are not the root cause of the condition.

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio