(Bloomberg) – Eurozone central banks are set to disclose their first significant losses from a decade of money printing in the coming weeks, ushering in a new era of scrutiny and the prospect of taxpayer bailouts.

Most read by Bloomberg

When the European Central Bank announces its full-year results on Thursday, officials are expected to warn of large deficits this year and next across the region as higher interest rates push up the cost of managing deposits built up by quantitative easing let go.

The ECB’s release will herald a slew of uncomfortable national reports, with Germany’s Bundesbank potentially facing the biggest hit of all.

“Outcomes will turn negative for many banks as early as 2022 as interest rates on assets and liabilities do not match,” Bank of Portugal Governor Mario Centeno said in an interview. “We are now funding ourselves at higher interest rates that are inconsistent with the yield on bonds and all types of debt on the central bank’s balance sheet.”

Losses in the euro zone would add to a list of examples around the world, with neighboring Swiss National Bank standing out for its record deficit last month. The prospect has made some officials nervous given the light they risk shining on the region’s financial assets and potential fiscal implications.

The Bank for International Settlements this month insisted that such outcomes don’t matter, that central banks can operate on negative equity and that they cannot go bankrupt. Most importantly, officials claim losses have no impact on monetary policy.

Still, the ECB has criticized currency deficits elsewhere in the European Union, and its own rules can oblige governments to shell out money for national central banks. It is even conceivable that the Frankfurt institution itself needs help.

The Bundesbank is likely to post small losses in 2022, which will rise to 26 billion euros in 2023 if ECB interest rates remain at current levels, according to Daniel Gros, board member at the Center for European Policy Studies in Brussels.

That would wipe out the 20 billion euros in provisions for losses from asset purchase programs and the 5 billion euros in capital and reserves. For a normal company, this could mean bankruptcy.

A spokesman for the Bundesbank initially declined to comment when asked by Bloomberg.

Gros expects a warning in the annual financial statements and that the Bundesbank will “quietly try to negotiate a capital injection from Berlin” this year.

However, in the latest string of repeated losses in the 1970s, officials rolled over the shortfall to subsequent years, raising the prospect that they might do so again.

Other counterparties also face big losses in 2023, but not enough to wipe out capital. Gros expects 17 billion euros in France, 9 billion euros in Italy and 5 billion euros in the Netherlands. If interest rates remain high in 2024, the Dutch and French central banks would also be at risk of negative equity.

In September, Dutch central bank governor Klaas Knot warned his government of “significant cumulative losses” in the coming years. “In extreme cases, a capital contribution” from the taxpayer “may be required,” he said.

Jerome Haegeli, chief economist at Swiss Re and a former SNB official, said losses would likely subject central banks and their money-printing programs to closer political and public scrutiny.

The combination of high inflation – attributed in part to QE by some – and all the taxpayer transfers needed to reverse negative capital positions can be viewed as a “super tax on economies,” he said.

“Together with central banks no longer providing windfall profits, this means that the public deficit is increasing,” he said. At worst, filling central bank funding gaps could mean governments “need even higher taxes.”

The dual impact puts central banks’ “most important asset, namely their de facto independence, at risk,” Haegeli said.

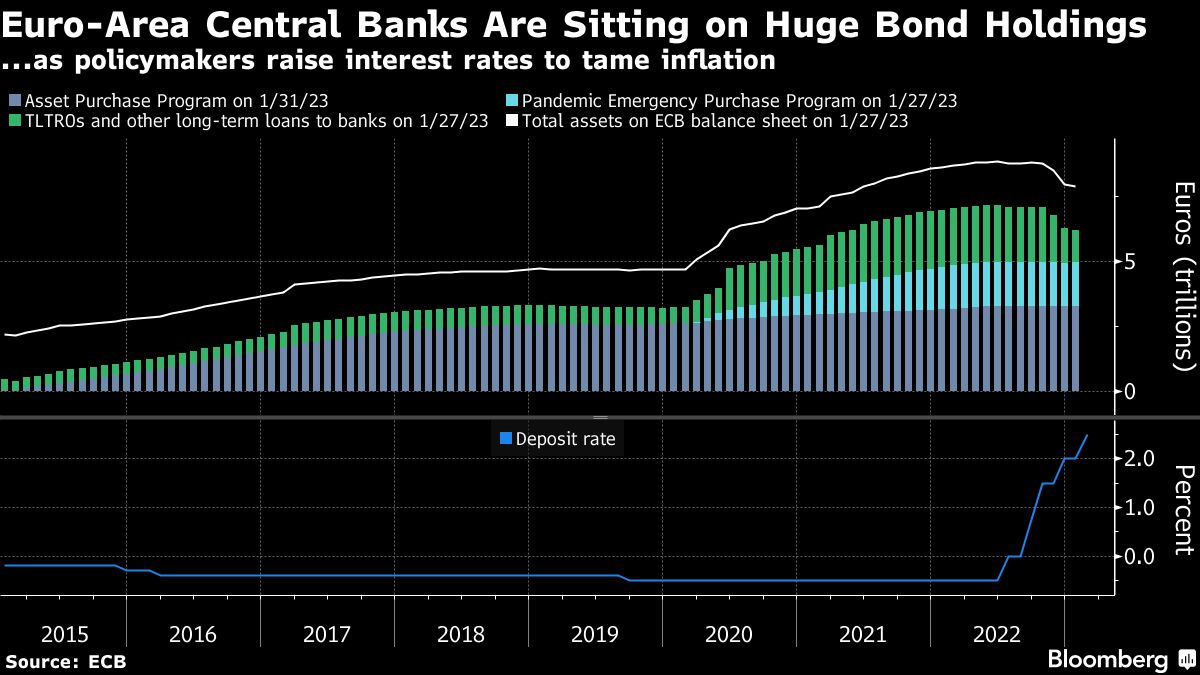

The losses come as the ECB injected liquidity, mostly buying €5 trillion worth of government bonds, to stoke inflation and stabilize financial markets during the pandemic. A large portion of these funds were repaid as deposits.

The national central banks remunerate them at the ECB rate, now 2.5%. The matching assets are fixed-rate bonds, which Gros says pays just 0.5% on average.

Although monetary decisions are made by the ECB, operations are conducted nationally. The Bundesbank has been hit hardest because German government bonds were seen as a safe haven with low or even negative yields. The Bank of Greece, whose purchases were much smaller and bought higher-yielding government bonds, should remain profitable.

The institutions of the euro area expected deficits. According to the ECB, the entire capital and precautionary buffer against losses in the overall system amounts to 229 billion euros. “Central banks have taken an enormous amount of provisioning in this short cycle of very good results,” Centeno said.

For years, those gains also helped fund government spending, and the reversal now means public funds may be needed to rebuild balance sheets.

In a nearby example, the UK has already approved a transfer of £11bn ($13.2bn) to the Bank of England under pre-arranged compensation.

The Swiss central bank didn’t need a capital boost after its biggest loss ever – equivalent to about a fifth of Swiss GDP. But the SNB has omitted an annual payment to authorities for only the second time, and officials have begun shrinking the balance sheet to limit future deficits.

A loss of AA$36.7 billion ($25.1 billion) at the Reserve Bank of Australia has left it with negative equity of A$12.4 billion. It said in June it hoped to rebuild reserves by retaining future profits and has not sought state money.

According to BIS boss Agustin Carstens, that’s fine. He said this month that even with negative equity central banks “can and have operated effectively”. “The bottom line is that central banks are not about profit, they are about the common good.”

Most Read by Bloomberg Businessweek

©2023 Bloomberg LP

Don’t miss interesting posts on Famousbio